Since the sexual assault cases from 2018 hit the news, the CPS and law enforcement have done a lot of heavy lifting to bring about effective disclosure of material in all criminal investigations.

It’s an epic effort and over 3 years into the process (at the time of writing) the industry is getting closer to achieving a successful and standardised approach. But more needs to be done.

Launched in 2018, The National Disclosure Improvement Plan is now in phase 3 which commenced in the summer of 2021.

Phase 2 was all about embedding a culture of change and continuous improvement. You can read a report on phase 2 here. In summary, lots of new reports, guidelines, training, and codes of practice have introduced national changes. The roll out of new tools should see time savings going forward when providing disclosable material, and there has been a reduction in the number of cases failing for disclosure reasons.

Disclosure is a still a minefield. The manual has 38 chapters. Those conducting investigations carry an element of fear that they will fall foul of the guidelines. And some still do.

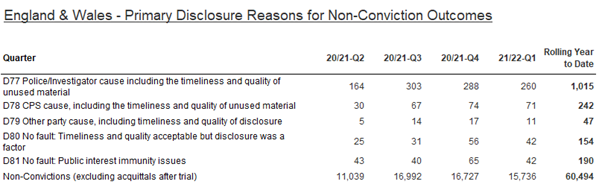

The latest figures suggest that the Investigator was the cause for non-convictions resulting from disclosure issues in over 1000 cases from June 2020 to 2021.

Source – https://www.cps.gov.uk/publication/cps-data-summary-quarter-1-2021-2022

Full disclosure of digital material, particularly mobile handsets is a difficult task. (see chapter 30). There is an extremely large amount of data that requires capturing, analysing, reviewing, and disclosing where appropriate. It can seemingly verge on the impossible but can often be resolved by considering the test of ‘reasonable lines of enquiry’.

The Court of Appeal recently issued a guideline judgement [in R v Bater-James and Mohammed] where digital content was under investigation. It identified four key principles for investigators to consider when balancing the needs of privacy of witnesses and complainants:

- Identifying the circumstances when it is necessary for investigators to seek details of a witness’s digital communications. The request to inspect digital material, in every case, must have a proper basis, usually that there are reasonable grounds to believe that it may reveal material relevant to the investigation or the likely issues at trial (“a reasonable line of inquiry”).

- How should the review of the witness’s electronic communications be conducted? The loss of a device for downloading for any period of time, may itself be an intrusion into the private life of an individual.

- What reassurance should be provided to the witness or complainant as to scale of the review and the circumstances of any disclosure of material that is relevant to the case?

- What is the consequence of a witness refusing to permit access to a potentially relevant device. either by downloading or permitting an officer to view data on the device and copying material, for instance by taking screen shots? Similarly, what are the consequences if the complainant deletes relevant material?

Growth in use of technology is the cause for how hard it now is, and it must also be the solution. That’s why improvements can be made with the current plan.

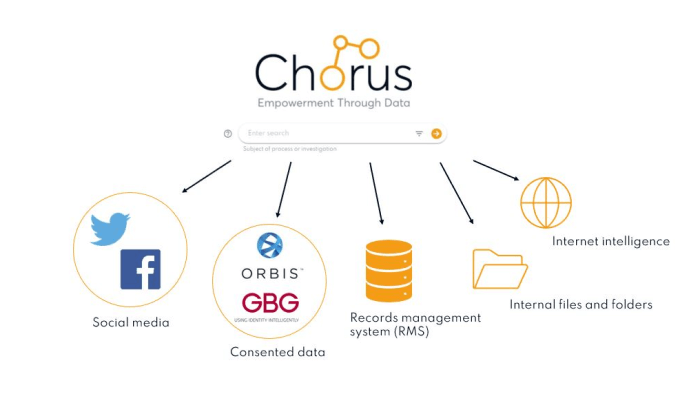

More engagement with technology providers is required. Yes, we might not be the size and scale of Adobe, but we were the first SME to enter into collaboration with the Police ICT Company and over 3000 Analysts and Investigators use our tools in the UK. There are other organisations out there like Chorus that provide tools for different stages of a digital investigation that also present fantastic solutions. We can all do our bit.

We are trying to build features into our Intelligence Suite that will help police staff address the disclosure principles. To be explicit about it, here are some of the things that we can do:

- Connect to and search all available data for names, numbers, other entities, and keep a record of that search. (Principle 1)

- Keep a copy of raw data (Principle 2)

- Instant redaction of telephone numbers in communications data analysis.(Principle 3 and 4)

- Capture open-source intelligence (web pages and social media feeds) as a searchable PDF.

- Carry out automated redaction of names, numbers, or any keyword.

- Log all URLs with a full audit trail to identify the source of the intelligence.

- Provide entity reports that clearly show the attribution of any contacts.

Especially looking at Chorus Search, you can reveal everything the police know about a particular entity. Collecting the intelligence can often be the biggest challenge with so many databases and sources of intelligence to check. A case can hinge on what the police can find. Chorus Search can link to it all and a decision made at source whether it is relevant or not.

All these things, and many other functions take some of the headache away from the Analyst or Investigator. Our outputs adhere to national file standards and follow the Attorney General’s guidelines where we can.

More and more responsibility has been handed down to Analysts and frontline Officers and they need time to be able to get through the number of documents and data that could impact the case. Disclosure has become everyone’s responsibility, and everyone should be looking at it from the early stages of an investigation.

With the reduction in police numbers, the duty to produce a disclosure schedule is now firmly with the Officer in Charge (OIC). The luxury of a central team that would curate case files is a long-lost memory. PCs working on their 1st case and long service DCs now have the same responsibilities in this area. This is not just a pressure on their time but also their availability to respond to new incidents. Likewise, the line manager needs to authorise the submission of case files and will be assessed on the quality.

One member of the Chorus team, Ben Peter, is an ex-response shift Sergeant from Essex Police who remembers the pressure that the switch from remotely created case files to the OIC created. ‘’The new role for the OIC came about very quickly which added huge time pressure to the front-line shift teams and supervisors. Not just the time to write the documents, but also the time to check through them while maintaining response capabilities. As an example, we attended huge numbers of domestic incidents. The need to safely redact documents and keep the victim safe was paramount. The tools we had were very basic and the methods always carried a risk of missing something’’.

We recognise there is no silver bullet for the digital disclosure problem, and we are only part of the solution. But we’ll continue to invest our time and energy into building tools that can help. Everything you do in the Chorus Intelligence Suite has a supporting document or an audit trail that should give our customers confidence in what they are doing.

Back to the level of engagement with technology providers and its one of the ambitions of the National Policing Digital Strategy. Point 5, empower the private sector. It happens, just not enough. We have some great tools that share the burden of getting through the mountain of data to ensure cases quickly reach a successful outcome. Involve us, talk to us, and let’s work together to make life easier for everyone and ultimately keep the streets a little bit safer.